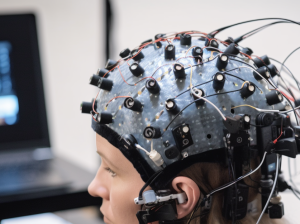

By all accounts, there were a lot of unexpected twists and turns during the Trumpfluenced election season of 2016. Predictions shattered, political norms dashed (and new words invented…). And, believe it or not, even a new vista in neuroscience! On June 23rd 2016, the Washinton Post reported on the research of Spencor Gerrol in trying to decipher voter unpredictability. Study participants wore head-gear gadgets measuring their emotional responses – through electroencephalograms (whatever those are!), galvanic skin responses (probably a fancy term for skin movements), eye tracking, and microfacial recognition (facial expressions?) – while viewing debates, interviews, and speeches. Instead of drawing conclusions from people’s conscious expressions, Gerrol’s techy setup harvested information directly from the brain.

By all accounts, there were a lot of unexpected twists and turns during the Trumpfluenced election season of 2016. Predictions shattered, political norms dashed (and new words invented…). And, believe it or not, even a new vista in neuroscience! On June 23rd 2016, the Washinton Post reported on the research of Spencor Gerrol in trying to decipher voter unpredictability. Study participants wore head-gear gadgets measuring their emotional responses – through electroencephalograms (whatever those are!), galvanic skin responses (probably a fancy term for skin movements), eye tracking, and microfacial recognition (facial expressions?) – while viewing debates, interviews, and speeches. Instead of drawing conclusions from people’s conscious expressions, Gerrol’s techy setup harvested information directly from the brain.

According to Gerrol, “What people feel and what they say they feel are rarely the same… Emotion is subconscious. The idea is to measure emotion without asking.”

For example: one participant said she supports Trump “because of his positions on immigration and spending… [but I] hate his behavior… he is a bully and not presidential at all!” However, the brain-activity headset – with its array of circular prongs – showed a different picture. While viewing a Trump-tirade against “Little Marco”, she exhibited strong, positive emotion.

Sounds perturbing, right?

But I cannot help but wonder if Gerrol and his team of neuroscientists inaccurately assumed that emotion is purely subconscious and hopelessly distorted when filtered into conscious expression.

From a Torah perspective, there is a dichotomy of components that comprise what we are. There is a body and a soul, a mind and a heart, a lower “I” and a higher “I”. There’s a well-known illustration of the master of mussar that can help a person discover the real “I”. It’s 6:30 am in the middle of February and the alarm is ringing. Your bed is super comfortable, you are really

But, wait; stop!! Who was that talking? Is it really true that you don’t want to wake up? Is that your true desire? Really? You don’t want to wake up? You don’t want to start off your day on the right foot?! Of course you do! Just what? You’re tired, so it’s hard. But does that justify a statement of “I don’t want to get up now”? What does your true “I” really want?

So who was that talking?

We all have our less lofty inclinations, what we often call the yetzer hara. And those inclinations tend to take on an awfully cunning form. In this world, we are constantly involved in the “melacha of borer”. We have the ability of sifting through the chaff and extract the good from the bad (or less good). We have the ability to examine ourselves and discover wherein lies the true “I”, and what is more an expression of our less lofty side.

Our goal is not to negate the animalistic facet of our being, but to harness it and place it squarely under the direction of the higher, true “I”.

In other words, the emotions that the brainwave detecting gadget picks up on in a given moment may not be presenting an accurate depiction of that person’s true, inner feelings.

We all find contradictions in ourselves on a regular basis. Perhaps we enjoyed listening to some juicy gossip, only to later regret such distasteful behavior. Or how about the shul-talkers. Inside, a person may be repulsed by it, but he might stumble anyway because, in the moment, the gossip “feels” good.

It’s not that we human beings are necessarily frauds. Expressions of dissonance do not mean that we are hypocrites. It’s simply the fact that we are a delicate and complex composite of disparate parts. And recognizing internal inconsistencies doesn’t need to be an impetus for harsh, self-incrimination. On the contrary, it can be an empowering opportunity to learn more about and get in touch with the true I, the higher I.