Fads are an interesting phenomenon, particularly amongst children. Take for example the recurring obsession with Rubik’s cubes. You can go from nary seeing those multi-colored squares to, all of a sudden, seeing practically every  boy and girl from ages four to eleven completely mesmerized by the six-sided puzzle. And, of course, any kid who actually masters the thing while the fad is ongoing will be regarded with admiration akin to hero worship.

boy and girl from ages four to eleven completely mesmerized by the six-sided puzzle. And, of course, any kid who actually masters the thing while the fad is ongoing will be regarded with admiration akin to hero worship.

The last time that we had a Rubik’s cube fad going on here in Israel, I assumed that it was a local phenomenon. But then I heard a shiur by Rav Fishel Schachter where he made reference to it in New York.

So it was international!

How a fad like that emerges all of a sudden out of nowhere on such a large scale, and with zero regard to the massive bodies of water that separate continents, is a conundrum no less confounding than a concurrent outbreak of a virulent virus across the world, albeit without the terror that the latter involves. No less mysterious – again, eerily akin to infamously infectious diseases – is the way these fads tend to vanish into thin air with just as much inexplicable swiftness as their arrival.

The phenomenon of fad-phases – their coming, going, and interim intensiveness of interest – is something, I think, that can give us pause to contemplate our human nature. Now, when it comes to Rubik’s cubes, slapsticks, or kugelach, it really is not all that significant (although there certainly is room for discussion regarding to what extent we ought to indulge our children these fads or utilize them as an opportunity to instill a bit of self-discipline and forbearance). But when it comes to what really matters in life – namely, how we go about functioning as frum Yidden – it assumes an import of powerful proportions.

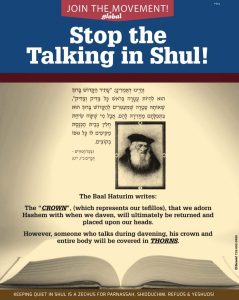

Let’s use the once-robust “Stop the Talking in Shul” campaign as an example. Whoever started it deserves tremendous credit. Particularly so for ensuring that the momentum increased in vigor for quite some time. For a much-longer-than-normal duration, they did not allow the campaign to wane or stagnate. For a while, it seemed to be taking on the dimensions of a real movement, which, at the time, was very inspiring and encouraging. That being said, I would like to draw attention to a sobering, real-life vignette (identifying details changed). Bear with me, my purpose is not to pour a bucket of cold water on the enthusiasm behind meaningful campaigns, but to highlight a potentially weak link in the chain.

At a certain point in the heyday of the “Stop the Talking in Shul” campaign, a video clip of Rabbi Zecharya

Here is where I must make my own confession.

When I noticed this man’s name on the flier posted in Shul, and being wholly unaware of what he was slated to talk about, I found myself thinking, “What?! This guy is going to speak at a chizuk event?! What a joke!” Boy did I learn a thing a two when I subsequently heard a report of the heartfelt words that this man shared. He candidly spoke of how he had been deeply entrenched in the rut of talking during davening, and how much he gained by quitting that awful habit. Perhaps most importantly, he shared with everyone how challenging this goal continues to be for him, and how he understands everyone else’s challenge as well. Particularly since the kehilla in which he is a member is so friendly and outgoing.

But here’s the not-so-happy part.

After about a month of a near 100% record of no talking during davening, the murmurs and whispers began slowly returning. And that particular man was not uninvolved. You see, his seat in Shul is right next to one of his best friends. And that had been one of the main causes of his talking problem to begin with. Truth be told, after this man made his public “confession”, many of his fellow Shul-goers expected that he would change his seat as a concrete way of ensuring that he follow through with his commitment. But he didn’t. And that seems to be the trigger for the reemergence of the talking problem.

Apropos to this discussion, I once heard a professional therapist offer a major insight into human behavior. He was discussing the role of motivation as a predictor of future behavior. It isn’t. “The greatest predictor of future behavior,” this therapist said, “is past behavior.”

Someone in the upsurge of tremendous inspiration and motivation can wax indignant at such a statement, but the fact is that if we really want to make changes for the better that will stick, we should take those words to heart.

So what does that mean? That there is no hope? Of course not. That same therapist continued, “Because motivation by nature can be so whimsical, there is no way to bank on it. At all. Motivation comes and goes. But good behaviors, we want them to continue even when the motivation is low, or entirely absent. And that,” he concluded, “only has a chance to occur if real changes are implemented that will necessarily alter the path of previously ingrained habits.”

Although that may sound like a chiddush, it really isn’t. Our Sages talked about it centuries ago. That is, the need for someone who has stumbled to come up with a solid, specific game-plan that will keep him far away from his source of temptation for the future. To erect protective fences that create a real, concrete barrier between him and the opportunity for reoffending.

We don’t want chizuk to be a passing fad. Something that makes a big splash for an isolated slice of time and then gets relegated to the dusty pile of great ideas that never properly materialized, isn’t really what we’re aiming at, is it? When we realize that there is something that demands improvement – whether on the communal or individual scale – we want to ensure that the positive changes we make will be lasting.

Permanent.

To do that, it is key to have awareness of a) the ephemeral nature of motivation, and b) the fact that past behavior is the strongest predictor of future behavior. To implement real, far-reaching change, we have to make real changes. Structural ones. For most people, a firm decision of the heart does not suffice. The situation itself has to undergo relevant change. Whether that means changing one’s makom kavuah, the Shul in which one davens, instituting a system by which people are given more kibbudim as a reward for exemplary behavior, or any other number of possible structural changes that can be made, something of that nature is definitely called for.

So remember this: we don’t want a fad, we want a “daf”. And to do that, real concrete change is the best way to go.